Crossing Things Out

Emily Yankowitz (Graduate student in History, Yale University)

Over the past few weeks, I’ve had several conversations with friends about the frustrations of handwriting a letter and making a mistake along the way.

You are plodding along, and then suddenly, your mind drifts to something else and you make a spelling error, or your pen accidently lingers too long and now there is a stray line. And then you find yourself contemplating if you can hide the mistake by altering neighboring letters or if it would be too obvious to cross the mistake out. The vast majority of the time, I decide that the error regardless of how tiny is beyond repair and I begin again–a particularly frustrating occurrence when the mistake was made near the end of the letter.

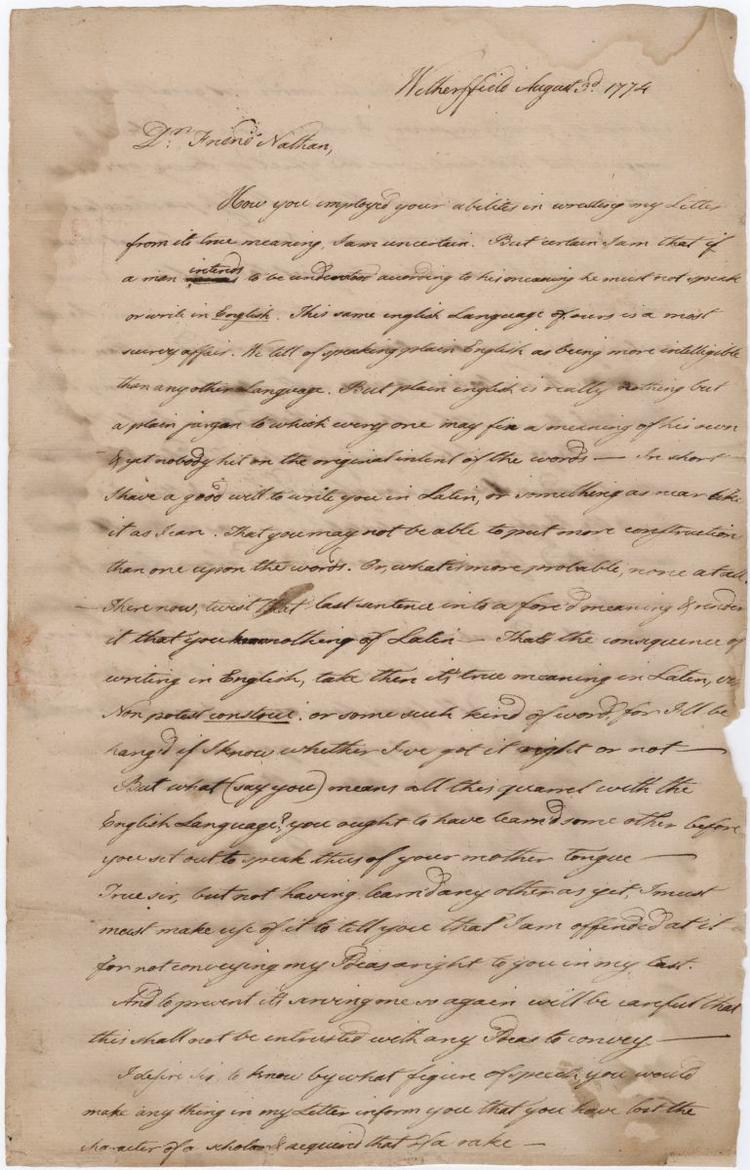

Shortly after one of these conversations, I came across Ebenezer Williams’ August 3, 1774 letter to Nathan Hale.

(Ebenezer Williams to Nathan Hale, August 3, 1774. Gen MSS 1146, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library)

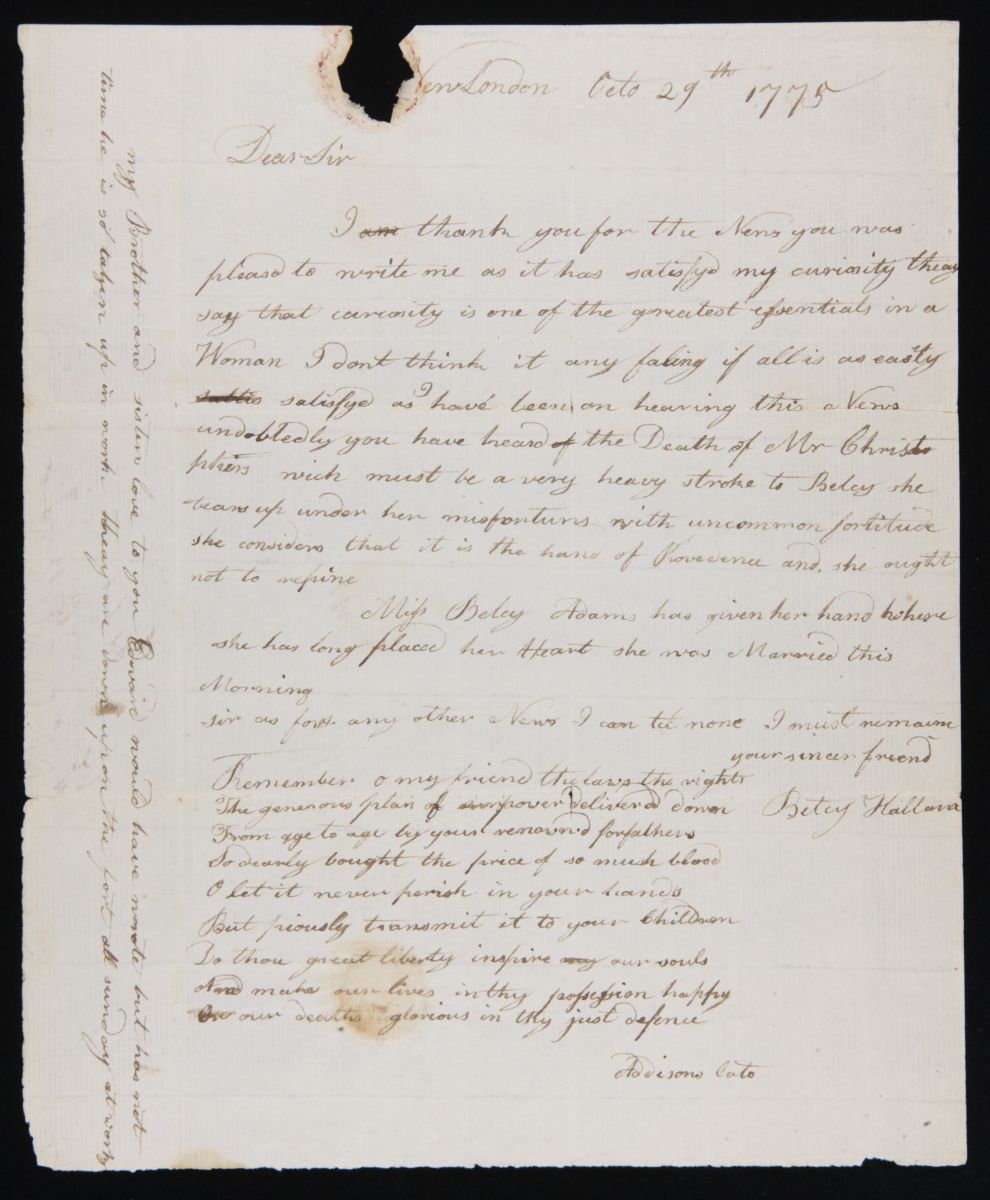

Followed shortly thereafter by Betsy Hallam’s October 29, 1775 letter to Nathan Hale.

(Betsy Hallam to Nathan Hale, October 29, 1775. Gen MSS 1146, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library)

Both letters are sent copies. While neither letter is riddled with errors, both contain crossed out words.

For example, in line three, Williams crosses out a word and writes “intends.” Further down in the letter, in line thirteen, Williams crosses out “know,” choosing to use the word “nothing” instead.

In the first line of Hallam’s letter, she crosses out “am,” so that the letter begins with “I thank you” rather than “I am thank you.” In the fifth line, Hallam crosses out “subtio,” and in the sixth line, she crosses out “of.” In her quotation from Addison’s Cato, Hallam crosses out “my” to write “our.”

While the letter is certainly not riddled with them, they are present in the sent copies of these letters.

Why?

One possible explanation points to the fact that Williams and Hale were friends. This explanation holds less true in the case of Hallam since she a one of the pupils Hale taught while in New London. In Hallam’s case, it is more likely the errors could be traced to her age or her limited schooling. Other reasons might include a desire to just send the letter, or the cost or limited availability of paper.

Regardless, the crossed out and inserted words in these letters serve as a reminder to me about the humanity of the people whose letters we read.