Amanda Mehsima Licato is a Ph.D. Candidate in English studying nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century American literature in the Department of English at Stanford University, with a focus on African American literature, print culture, and poetry and poetics. Her dissertation, “Out from Behind this Mask”: Persona in African American Poetry, 1830-1930, leverages a formal attention to masking in the poetic tradition to analyze African American lyric and its historical contexts from the slave era and Jim Crow era.

On January 10, 1934, the painter Georgia O’Keeffe confided in a letter to the writer Jean Toomer:

Maybe the quality that we have in common is relentlessness — maybe the thing that attracts me to you separates me from you — a kind of beauty that circumstance has developed in you — and that I have not felt the need of till now … I like knowing the feel of your maleness — and your laugh.[i]

Jean Toomer and Georgia O’Keeffe were two great searchers of American modernism, discovering each other as well as new forms for the subjects of their art in the early-to-mid twentieth century. A yet untold juncture of this relationship, surprisingly obscure even among Toomer and O’Keeffe enthusiasts and scholars—an intimate tryst beginning in the winter of 1933—has remained buried in correspondence currently housed in the Jean Toomer Papers at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. These letters reveal Toomer and O’Keeffe’s short-lived romance, which came after almost a decade of friendship. They also allow us to more fully grasp the parallel paths Toomer and O’Keeffe followed as artistic figures who felt misunderstood by the art world, and who fought to remove themselves from their prescribed artistic labels—Toomer as an African American artist who embodied the black principle and O’Keeffe as a female artist who embodied the feminine principle. Through these letters, we witness Toomer and O’Keeffe’s nurturing of an intimacy that reassured them both of their artistic and personal value.

When Jean Toomer and Georgia O’Keeffe met in the early 1920s, they had already gained widespread recognition for projects that entangled them in the racial and gender associations of their era. The popularization of Freud was in large part responsible for the renown of O’Keeffe’s magnified-flower paintings, which she first experimented with around 1921; flowers had become the ideal not of innocence but of erotic feeling.[ii] O’Keeffe bristled at this line of interpretation: “…when you took time to really notice my flower you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower, and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower—and I don’t.”[iii] Even during her time, O’Keeffe became representative of a sexual principle that she felt very much at odds with. A substantial portion of the later work that she produced—in the world of steel and glass with her New York skyscraper series, or in the wild countryside of New Mexico with her skull paintings—was thus a conscious attempt to engage with the reception of her early work and the gendered spaces of the art world. Such would be her provocation to paint: “Before I put a brush to canvas I question, ‘Is this mine? Is it all intrinsically of myself? Is it influenced by some idea or some photograph of an idea which I have acquired from some man?’”[iv] Despite this resistance, popular reception of O’Keeffe’s aesthetic has largely remained with her magnified-flower series, where she forged a sophisticated manipulation of space with a vibrant use of color.

Toomer too experienced the limitations of being categorized. In 1924, he wrote to O’Keeffe:

Have you come to the story “Bona and Paul” in Cane? Impure and imperfect as it is, I feel that you…will catch its essential design as no [one] can. Most people cannot see this story because of the inhibitory baggage they bring with them. When I say white they see a certain white man, when I say black they see a certain Negro. Just as they miss Stieglitz’s intentions, achievements! because they see “clouds.”[v]

Toomer’s reference to the prominent photographer, Alfred Stieglitz (notably O’Keeffe’s husband), and the “clouds” in Stieglitz’s Equivalents, a series of photographs begun in 1922 of clouds and sky, suggests that Toomer believed his audience would confine his fiction by bringing in their own “inhibitory baggage” of character types and race relations. Toomer’s apprehension had manifested amidst the backdrop of the Harlem Renaissance and the publication of his first novel, Cane, considered a hallmark of African American modernism.[vi] The publication of the novel set off a strangely conflicted success for Toomer: the first printing was of only 500 copies, sales were low, and the book was not widely read. However, the novel did receive general praise, marked by a substantial ignorance of Toomer’s uneasiness in being identified as black. Toomer’s mixed racial identity proved to be a persistent issue throughout his life, even though he was raised by his maternal grandfather, P. B. S. Pinchback, the first African American to become governor of a U.S. state. Only decades after Toomer’s reaction to Cane’s initial reception became known in small literary circles did critics gain a new perspective and sensitivity to Toomer’s ambivalence at having both himself and his work strictly classified as African American. Toomer believed that O’Keeffe, also attuned to abstract sensibilities, would catch on to this sensitivity and the subtle aesthetic design of his work like few could.

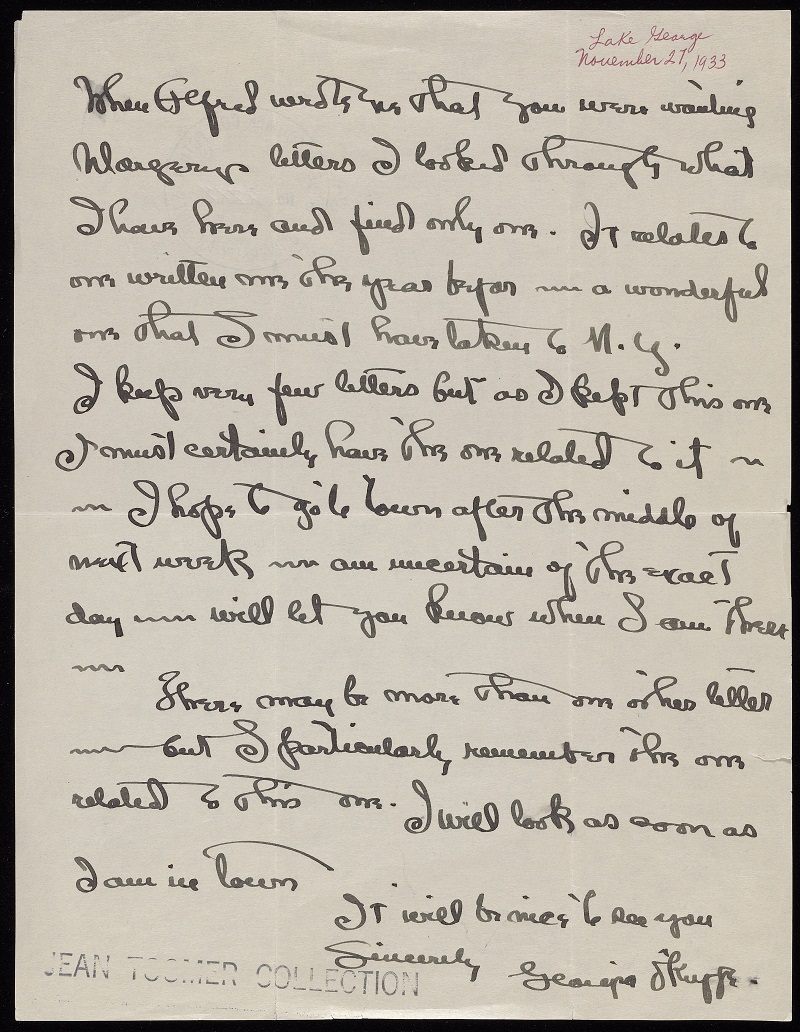

In November 1933, Toomer wrote to O’Keeffe to ask her if she had any of his wife Margery Latimer’s letters. The year prior, Latimer had died in childbirth; his plan was to publish a volume of her writings. O’Keeffe, who was recovering at Lake George after being admitted in early 1933 for psychoneurosis at Doctors Hospital, explained that she didn’t save letters but might have one in New York. “It will be nice to see you,” she wrote on November 27, pleased that Toomer had accepted her invitation to visit the house that she shared with her husband, Stieglitz, at Lake George.

When Toomer arrived, he and O’Keeffe resided alone in the farmhouse from late November until the New Year. For the first week, Toomer worked in solitude on a new manuscript. “He is nice to have about — Is working on a novel — but we say a few words a day to one another and get on very well,” O’Keeffe wrote to Rebecca Strand in December. In a series of letters to Stieglitz, Toomer let him know of O’Keeffe’s improving health, and then, abruptly, of a dramatic change:

I am amazed at the way Georgia has suddenly come out of that condition into this condition, this aliveness. For the first ten days I was sort of in the house by myself….Now it is inhabited by someone else, by an extraordinary person whom, hitherto, I’ve hardly more than peeped at from the outside (and how she can keep people outside!), whom now, however, I’m beginning to see and feel — if not to understand! We’ve had several long talks about all sorts of things and I’m impressed at the way she has of remaining always herself. (Dec. 22, 1933)

In the last days of December, the relationship between Toomer and O’Keeffe had deepened in an unpredictable way. When Toomer left in early January, the two began to write each other tender letters that revealed what the interlude had meant to them, with notes exchanged weeks, often days, apart from one another.

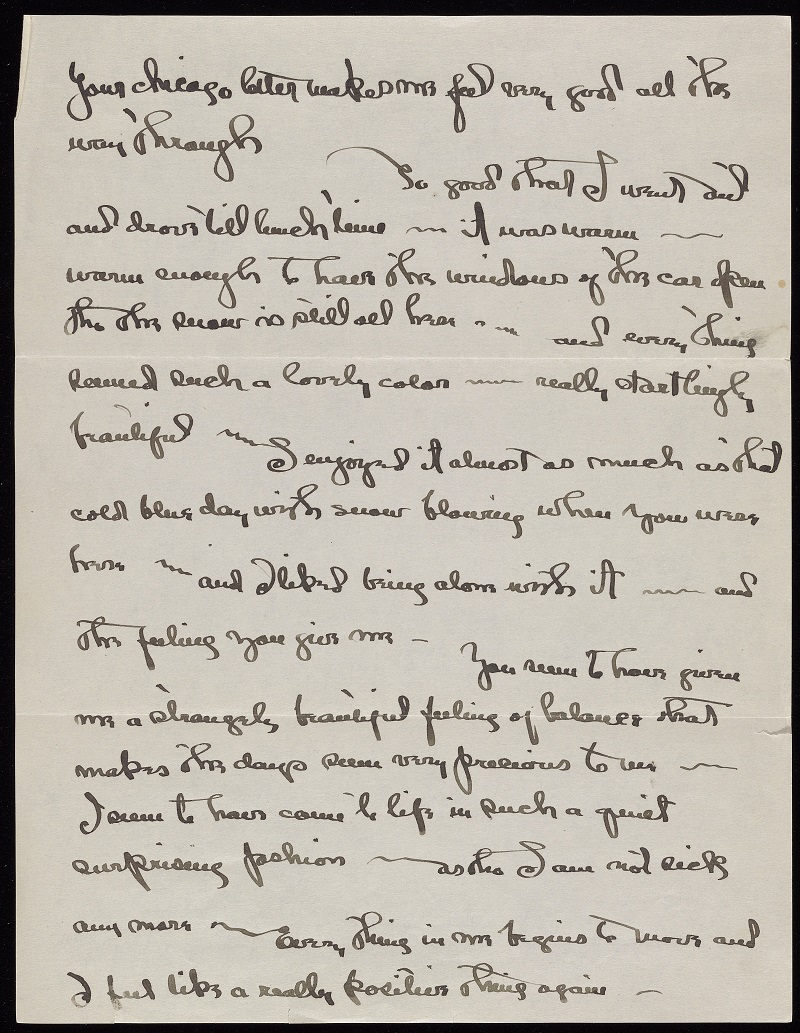

O’Keeffe reflected on Toomer’s meditative gaze, of the feelings he had expressed that had restored her:

You seem to have given me a strangely beautiful feeling of balance that makes the days seem very precious to me — I seem to have come into life in such a quiet surprising fashion — as though I am not sick anymore —Everything in me begins to move and I feel like a really positive thing

again. (Jan. 3, 1934)

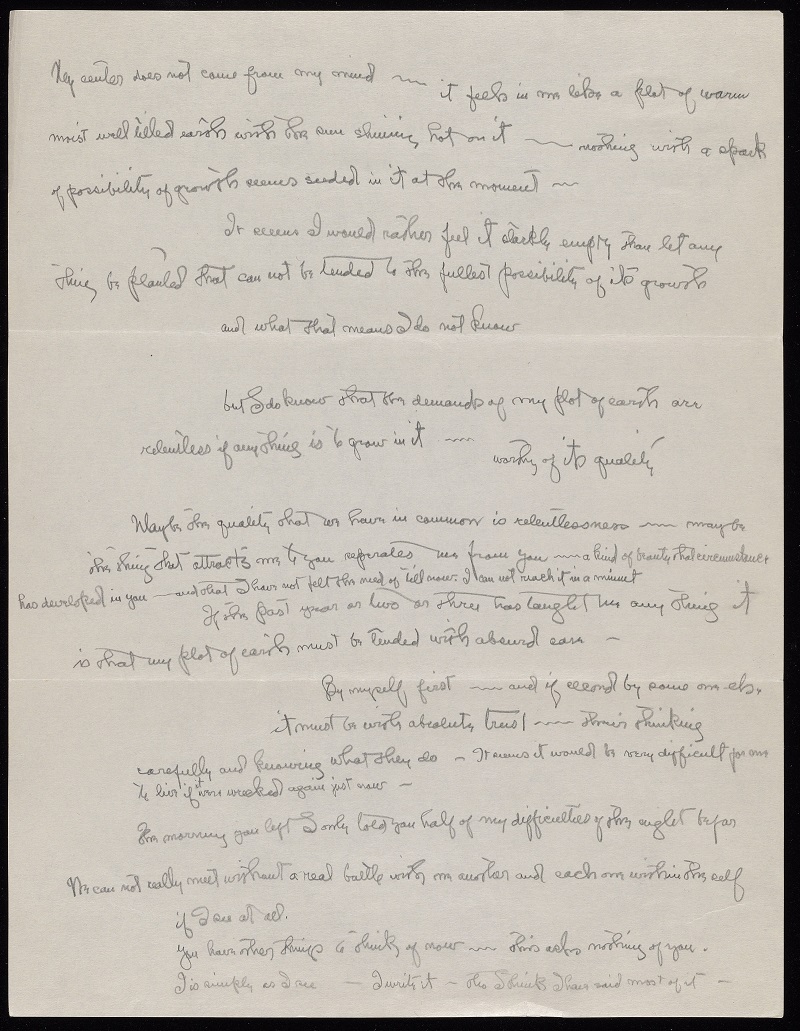

Often erotic, their letters surprisingly make clear that they had become lovers. “I miss you…so many things seem to have turned over in me that it seems a very long time [since you left],” Georgia wrote to him, and even more sensually, “I wish so hotly to feel you hold me very tight — and warm to you”. Toomer intimated his affection on January 4: “Greetings to…the bundling-bed” (bundling was a nineteenth-century practice that wrapped one person in blankets so that in the event of a shared bed, a couple could retain intimacy but also prevent intercourse). O’Keeffe, however, hastily implied that there was a more severe gap between them that could never be bridged, something that prevented the affair from continuing after Toomer’s departure. On January 10, she wrote of a dream about him with another woman:

I waked this morning with a dream about you just disappearing — As I seemed to be waking you were leaning over me as you sat on the side of my bed the way you did the night I went to sleep and slept all evening in the dining room — I was warm and just rousing myself with the feeling of you bending over me — when someone came for you — I wasn’t quite awake yet — seemed to be in my room upstairs — doors opening and closing in the hall and to the bathroom — whispers — a womans slight laugh — a space of time — then I seemed to wake and realize you had gone out and that the noises I had heard in my half sleep undoubtedly meant that you had been in bed with her…The morning you left I only told you half of my difficulties of the night before. We can not really meet without a real battle with one another and each one within the self — if I see at all. You have other things to think of now.

The intense vulnerability of this letter, tinged with jealousy on O’Keeffe’s end, hints at the paradoxical nature of their relationship. On the one hand, both clearly felt a need to testify their love for each other in their ongoing involvement; on the other, the letters draw out an oddity of intimacy as both attempted to navigate the language of vulnerability. O’Keeffe insinuated a resistance to this vulnerability, in that the demands of her own self-worth refused the attachment of another: “If the past year or two has taught me anything,” she wrote, “it is that my plot of earth must be tended with absurd care — By myself first.” The relationship, mysteriously, had reached its romantic limits; there was nothing left to test or wonder. Yet despite this inability to advance as lovers beyond the limits of Lake George, Toomer and O’Keeffe returned to the outside world with a sense of deep and necessary commitment to their own needs:

What you give me makes me feel more able to stand up alone—and I would like to feel able to stand up alone before I put out my hand to anyone—Maybe what you give me at this time and in this way is the most precious thing I can receive from you.

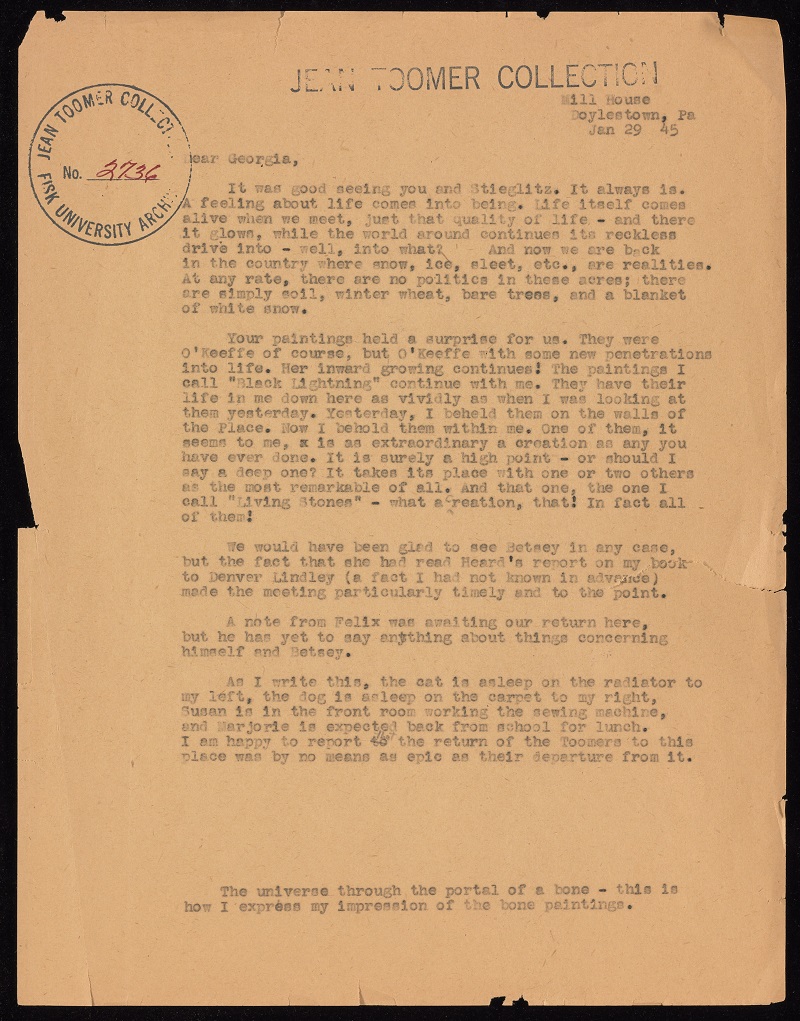

Toomer last wrote to O’Keeffe on January 29, 1945 after viewing an exhibition of her skull paintings at Stieglitz’s The Place:

Your paintings held a surprise for me. They were O’Keeffe of course, but O’Keeffe with some new penetrations into life…They have their life in me down here as vividly as when I was looking at them yesterday. Yesterday, I beheld them on the walls of the Place. Now I behold them within me.

Toomer understood the transformation of the animal bones that O’Keeffe collected near her second home in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico: smooth shapes metamorphosed into a monumental metaphor of the land and of life. His striking remark on holding O’Keeffe’s paintings within him recalls a line that O’Keeffe wrote him in 1934 during the height of their affair: “We can not really meet without a real battle with one another and each one within the self.” In the final letter from their correspondence, Toomer reminisced of when they last saw each other: “Life itself comes alive when we meet, just that quality of life — and there it flows, while the world around continues its reckless drive into — well, into what?” Toomer and O’Keeffe had chased after, and found, “life itself.” They discovered an affection and confidence in one another, so close that their interactions created a closed system, separate from the matters of the outside world. Toomer’s use of present tense, even though they had not seen each other for years, and perhaps never did again, reverberates the memories shared between them. Both emerged from the twenties as significant and critically misunderstood artists. And though O’Keeffe more clearly, and perhaps more darkly, found herself as an artist in the course of her career, Toomer’s later legacy, chiefly because of a crucial lack of interest in his work following Cane, still remains open, as does the question of what the artistic destinies of Jean Toomer and Georgia O’Keeffe would have been had they never met.

Call Number: JWJ MSS 1 (Series 1, Correspondence: Box 6, Folder 204)

[i] Georgia O’Keeffe to Jean Toomer, Jan. 10, 1934.

[ii] In 1921, Stieglitz’s nude photographic portraits of O’Keeffe were made public.

[iii] Calvin Tomkins. “The Rose is the Eye Looked Pretty Fine,” The New Yorker, March 4, 1974.

[iv] O’Keeffe, qtd. in “Is Art Life? Is Life Art? They Disagree: Radical Writer and Woman Artist Clash on Propaganda and Its Uses,” New York World, 16 March 1930.

[v] Frederik Rusch, A Jean Toomer Reader (New York: Oxford UP, 1993): 280-81.

[vi] Cane has a significantly ambitious and nontraditional form, structured as a series of vignettes. Though some characters and phrases reappear between these vignettes, they are mostly freestanding and imagistic.